An Overview of the Holocaust

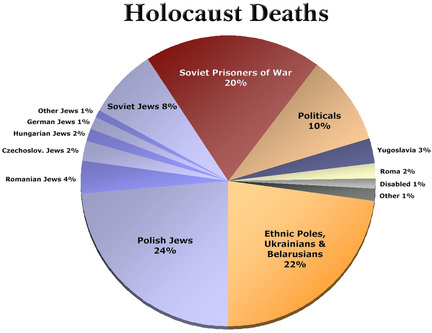

The Holocaust was the systematic, bureaucratic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of approximately six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its

collaborators. "Holocaust" is a word of Greek origin meaning "sacrifice by fire." The Nazis, who came to power in Germany in January 1933, believed that

Germans were "racially superior" and that the Jews, deemed "inferior," were an alien threat to the so-called German racial community.

During the era of the Holocaust, German authorities also targeted other groups because of their perceived "racial inferiority": Roma (Gypsies), the disabled, and some of the Slavic peoples (Poles, Russians, and others). Other groups were persecuted on political, ideological, and behavioral grounds, among them

Communists, Socialists, Jehovah's Witnesses, and homosexuals.

In the final months of the war, SS guards moved camp inmates by train or on forced marches, often called “death marches,” in an attempt to prevent the

Allied liberation of large numbers of prisoners. As Allied forces moved across Europe in a series of offensives against Germany, they began to encounter and liberate concentration camp prisoners, as well as prisoners en route by forced march from one camp to another. The marches continued until May 7, 1945, the day the German armed forces surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. For the western Allies, World War II officially ended in Europe on the next day, May 8 (V-E Day), while Soviet forces announced their “Victory Day” on May 9, 1945.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, many of the survivors found shelter in displaced persons (DP) camps administered by the Allied powers. Between 1948 and 1951, almost 700,000 Jews emigrated to Israel, including 136,000 Jewish displaced persons from Europe. Other Jewish DPs emigrated to the United States and other nations. The last DP camp closed in 1957. The crimes committed during the Holocaust devastated most European Jewish communities and eliminated hundreds of Jewish communities in occupied eastern Europe entirely.

collaborators. "Holocaust" is a word of Greek origin meaning "sacrifice by fire." The Nazis, who came to power in Germany in January 1933, believed that

Germans were "racially superior" and that the Jews, deemed "inferior," were an alien threat to the so-called German racial community.

During the era of the Holocaust, German authorities also targeted other groups because of their perceived "racial inferiority": Roma (Gypsies), the disabled, and some of the Slavic peoples (Poles, Russians, and others). Other groups were persecuted on political, ideological, and behavioral grounds, among them

Communists, Socialists, Jehovah's Witnesses, and homosexuals.

In the final months of the war, SS guards moved camp inmates by train or on forced marches, often called “death marches,” in an attempt to prevent the

Allied liberation of large numbers of prisoners. As Allied forces moved across Europe in a series of offensives against Germany, they began to encounter and liberate concentration camp prisoners, as well as prisoners en route by forced march from one camp to another. The marches continued until May 7, 1945, the day the German armed forces surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. For the western Allies, World War II officially ended in Europe on the next day, May 8 (V-E Day), while Soviet forces announced their “Victory Day” on May 9, 1945.

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, many of the survivors found shelter in displaced persons (DP) camps administered by the Allied powers. Between 1948 and 1951, almost 700,000 Jews emigrated to Israel, including 136,000 Jewish displaced persons from Europe. Other Jewish DPs emigrated to the United States and other nations. The last DP camp closed in 1957. The crimes committed during the Holocaust devastated most European Jewish communities and eliminated hundreds of Jewish communities in occupied eastern Europe entirely.

Pre-War Life

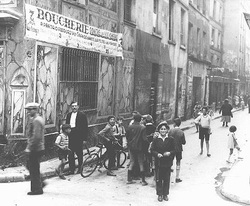

In 1933 the largest Jewish populations were concentrated in eastern Europe, including Poland, the Soviet Union, Hungary, and Romania. Many of the Jews of eastern Europe lived in predominantly Jewish towns or villages, called

shtetls. Eastern European Jews lived a separate life as a minority within the culture of the majority. They spoke their own language, Yiddish, which combines elements of German and Hebrew. They read Yiddish books, and attended

Yiddish theater and movies. Although many younger Jews in larger towns were beginning to adopt modern ways and dress, older people often dressed traditionally, the men wearing hats or caps, and the women modestly covering

their hair with wigs or kerchiefs.

In comparison, the Jews in western Europe—Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium—made up much less of the population and tended to adopt the culture of their non-Jewish neighbors. They dressed and talked like their countrymen, and traditional religious practices and Yiddish culture played a less important part in their lives. They tended to have had more formal education than eastern European Jews and to live in towns or cities.

Jews could be found in all walks of life, as farmers, tailors, seamstresses, factory hands, accountants, doctors, teachers, and small-business owners. Some

families were wealthy; many more were poor. Many children ended their schooling early to work in a craft or trade; others looked forward to continuing their

education at the university level. Still, whatever their differences, they were the same in one respect: by the 1930s, with the rise of the Nazis to power in

Germany, they all became potential victims, and their lives were forever changed.

shtetls. Eastern European Jews lived a separate life as a minority within the culture of the majority. They spoke their own language, Yiddish, which combines elements of German and Hebrew. They read Yiddish books, and attended

Yiddish theater and movies. Although many younger Jews in larger towns were beginning to adopt modern ways and dress, older people often dressed traditionally, the men wearing hats or caps, and the women modestly covering

their hair with wigs or kerchiefs.

In comparison, the Jews in western Europe—Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium—made up much less of the population and tended to adopt the culture of their non-Jewish neighbors. They dressed and talked like their countrymen, and traditional religious practices and Yiddish culture played a less important part in their lives. They tended to have had more formal education than eastern European Jews and to live in towns or cities.

Jews could be found in all walks of life, as farmers, tailors, seamstresses, factory hands, accountants, doctors, teachers, and small-business owners. Some

families were wealthy; many more were poor. Many children ended their schooling early to work in a craft or trade; others looked forward to continuing their

education at the university level. Still, whatever their differences, they were the same in one respect: by the 1930s, with the rise of the Nazis to power in

Germany, they all became potential victims, and their lives were forever changed.

What Led to Conflict

The start of the Holocaust was the combined result of many factors: "racism, combined with centuries-old

bigotry, renewed by a nationalistic fervor which emerged in Europe in the latter half of the 19th century, fueled by Germany's defeat in World War I and its national humiliation following the Treaty of Versailles, exacerbated by worldwide

economic hard times, the ineffectiveness of the Weimar Republic, and international indifference, and catalyzed by the political charisma, militaristic inclusiveness, and manipulative propaganda of Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime, contributed to the eventuality of the Holocaust."

Ravaged by World War I, the German state was already in poor economic shape before the Depression of the 1920's struck. Reparations demands and a weakened infrastructure led to inflation and unemployment. The democratic institutions artifically established by the Allies and a feeling of global alienation as a result of a guilt clause and land seizures in the Treaty of Versailles exacerbated social turmoil and left Germany looking for someone to blame.

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler, leader of the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party, was named chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg after the Nazi party won a significant percentage of the vote in the elections of 1932. The Nazi Party had taken advantage of the political unrest in Germany to gain an electoral foothold. The Nazis incited clashes with the communists and conducted a vicious propaganda campaign against its political opponents - the weak Weimar government and the Jews whom the Nazis blamed for Germany's ills.

bigotry, renewed by a nationalistic fervor which emerged in Europe in the latter half of the 19th century, fueled by Germany's defeat in World War I and its national humiliation following the Treaty of Versailles, exacerbated by worldwide

economic hard times, the ineffectiveness of the Weimar Republic, and international indifference, and catalyzed by the political charisma, militaristic inclusiveness, and manipulative propaganda of Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime, contributed to the eventuality of the Holocaust."

Ravaged by World War I, the German state was already in poor economic shape before the Depression of the 1920's struck. Reparations demands and a weakened infrastructure led to inflation and unemployment. The democratic institutions artifically established by the Allies and a feeling of global alienation as a result of a guilt clause and land seizures in the Treaty of Versailles exacerbated social turmoil and left Germany looking for someone to blame.

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler, leader of the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party, was named chancellor of Germany by President Paul von Hindenburg after the Nazi party won a significant percentage of the vote in the elections of 1932. The Nazi Party had taken advantage of the political unrest in Germany to gain an electoral foothold. The Nazis incited clashes with the communists and conducted a vicious propaganda campaign against its political opponents - the weak Weimar government and the Jews whom the Nazis blamed for Germany's ills.

Life During Conflict

During the Holocaust between 1.1 and 1.5 million children were murdered. These were Jewish, Romani (Gypsy), German children with disabilities, mental and physical, Polish or children who did not fit the "perfect" Aryan race. Hitler's plan was to create the perfect race. Jewish and non-Jewish children's fate fell into five major categories: 1. The children were killed when they arrived at killing centers. 2. Children were murdered directly after birth or in an institution. 3. Children born in ghettos and camps survived because prisoners hid them. 4. Children, typically over the age of twelve, were used as laborers and as mental experiments for camp doctors. 5. Lastly the children who were killed during reprisal operations or anti-partisan operations.

When the ghettos were formed many children who lived in the ghettos died due to starvation, exposure, un-propper clothing and poor shelter. To the Germans children in the ghettos were "useless" if they were too young to work as laborers in camps. Because they were too young to work, children, as well as the ill, elderly and disabled were the first groups to be shipped off to killing centers or the first to be shot into mass graves.

In the ghettos a council known as Judenrat was put in place to keep the order. These were Jewish elders who had to make life or death, moral or immoral decisions based on their own people. A horrific example of the Judenrat was sending children to Chelmno, a killing center in September 1942. The Judenrat also selected the children to be victims of mass grave shootings. Some of the older members of the Jewish ghettos did not chose their own lives to sacrifice children, but went to the killing centers with them. A man named Janusz Korczak, director of an orphanage in the Warsaw ghetto, refused to let the children go on without him under his care and was murdered in the gas chambers with his orphans.

When children arrived at concentration and transit camps they were incarcerated. In the concentration camps German physicians used children, especially twins, in medical research studies and experiments that more often than not ended in death. If the children were not chosen to be experiments they were put to work in unfit conditions and typically separated from their parents or killed immediately by gas or shooting.

Although children were vulnerable, terrified, and separated from their families, they did find ways to survive. Children smuggled food, medicine and personal items into the ghettos. Children participated in resistance activities and some children even escaped with parents or other relatives and in some cases escaped on their own. Another form of resistance was the Clandestine schools in the ghettos and the concentration camps. Between 1938 and 1940 the Kindertransport brought thousands of jewish children, without their parents, to the safety of Great Britain. In France, almost the entire Protestant population, as well as many Catholic priests, nuns, and lay Catholics, hid Jewish children in the town from 1942 to 1944. In Italy and Belgium, many children survived in hiding. The children in hiding often had to remain silent or even motionless in their hiding places for hours at a time. Both children and their protectors lived in constant fear and suspicion of their neighbors. If the protectors helping out and hiding Jews were to be captured they would not be spared by the Nazis.

During the Holocaust many children kept diaries and from these we have personal testimonies of child experiences. Most of the diaries and journals fall into three main categories:

1. Those written by children who escaped German controlled areas and became refugees and partisans. 2. Written by children living hiding. 3. Written by young people as ghetto residents, persons living under other restrictions imposed by German authorities, or more rarely as concentration camp prisoners.

The diaries written by children give us a look at what life was like in the ghettos, camps and the struggles they endeared. The diaries written by children in the ghettos show the first hand account of cruelty by the Nazi persecution, segregation, isolation, and vulnerability. Also they show the extreme suffering the Jews living in the ghettos went through. But on a positive side the children tried to distract themselves with play, creativity and study.

When the ghettos were formed many children who lived in the ghettos died due to starvation, exposure, un-propper clothing and poor shelter. To the Germans children in the ghettos were "useless" if they were too young to work as laborers in camps. Because they were too young to work, children, as well as the ill, elderly and disabled were the first groups to be shipped off to killing centers or the first to be shot into mass graves.

In the ghettos a council known as Judenrat was put in place to keep the order. These were Jewish elders who had to make life or death, moral or immoral decisions based on their own people. A horrific example of the Judenrat was sending children to Chelmno, a killing center in September 1942. The Judenrat also selected the children to be victims of mass grave shootings. Some of the older members of the Jewish ghettos did not chose their own lives to sacrifice children, but went to the killing centers with them. A man named Janusz Korczak, director of an orphanage in the Warsaw ghetto, refused to let the children go on without him under his care and was murdered in the gas chambers with his orphans.

When children arrived at concentration and transit camps they were incarcerated. In the concentration camps German physicians used children, especially twins, in medical research studies and experiments that more often than not ended in death. If the children were not chosen to be experiments they were put to work in unfit conditions and typically separated from their parents or killed immediately by gas or shooting.

Although children were vulnerable, terrified, and separated from their families, they did find ways to survive. Children smuggled food, medicine and personal items into the ghettos. Children participated in resistance activities and some children even escaped with parents or other relatives and in some cases escaped on their own. Another form of resistance was the Clandestine schools in the ghettos and the concentration camps. Between 1938 and 1940 the Kindertransport brought thousands of jewish children, without their parents, to the safety of Great Britain. In France, almost the entire Protestant population, as well as many Catholic priests, nuns, and lay Catholics, hid Jewish children in the town from 1942 to 1944. In Italy and Belgium, many children survived in hiding. The children in hiding often had to remain silent or even motionless in their hiding places for hours at a time. Both children and their protectors lived in constant fear and suspicion of their neighbors. If the protectors helping out and hiding Jews were to be captured they would not be spared by the Nazis.

During the Holocaust many children kept diaries and from these we have personal testimonies of child experiences. Most of the diaries and journals fall into three main categories:

1. Those written by children who escaped German controlled areas and became refugees and partisans. 2. Written by children living hiding. 3. Written by young people as ghetto residents, persons living under other restrictions imposed by German authorities, or more rarely as concentration camp prisoners.

The diaries written by children give us a look at what life was like in the ghettos, camps and the struggles they endeared. The diaries written by children in the ghettos show the first hand account of cruelty by the Nazi persecution, segregation, isolation, and vulnerability. Also they show the extreme suffering the Jews living in the ghettos went through. But on a positive side the children tried to distract themselves with play, creativity and study.

The Aftermath

At the end of the Holocaust, millions of people had died. However, many more were saved when the war ended. 80,000 Jews were freed from Budapest, 66,000 left from Auschwitz, 40,000 were freed from Bergen-Belsen, and thousands and thousands of others were released elsewhere.

Knowing his cause was hopeless, Adolf Hitler took his own life on April 30, 1945. Meanwhile, after World War II, many charges were put forth against the leaders of the Nazi party including Conspiracy, Crimes Against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes Against Humanity. Many of the Nazi Party's top executives were found guilty at the trial and were sent to the death chamber. Many more Nazi scientists and doctors as well as SS Einsatz leaders were tried at Nuremburg. Some of those individuals were killed. Overall, around six million people were killed in the Holocaust.

The killing of these people not only took the lives of these six million people, it also affected millions and millions of other people who loved these Jews.

After liberation, many Jewish survivors feared to return to their former homes because of the antisemitism (hatred of Jews) that persisted in parts of Europe and the trauma they had suffered. Some who returned home feared for their lives. In postwar Poland, for example, there were a number of pogroms (violent anti-Jewish riots). The largest of these occurred in the town of Kielce in 1946 when Polish rioters killed at least 42 Jews and beat many others.

With few possibilities for emigration, tens of thousands of homeless Holocaust survivors migrated westward to other European territories liberated by the western Allies. There they were housed in hundreds of refugee centers and displaced persons camps such as Bergen-Belsen in Germany. The United Nations

Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the occupying armies of the United States, Great Britain, and France administered these camps.

A considerable number and variety of Jewish agencies worked to assist the Jewish displaced persons. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee provided Holocaust survivors with food and clothing, while the Organization for Rehabilitation through Training (ORT) offered vocational training. Refugees also formed their

own organizations, and many labored for the establishment of an independent Jewish state in Palestine.

The Jewish Brigade Group (a Palestinian Jewish unit of the British army) was formed in late 1944. Together with former partisan fighters displaced in central

Europe, the Jewish Brigade Group created the Brihah, an organization that aimed to facilitate the exodus of Jewish refugees from Europe to Palestine. Jews already living in Palestine organized "illegal" immigration by ship. British authorities intercepted and turned back most of these vessels, however. In 1947 the British forced the ship Exodus 1947, carrying 4,500 Holocaust survivors headed for Palestine, to return to Germany. In most cases, the British detained Jewish refugees denied entry into Palestine in detention camps on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

With the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, Jewish displaced persons and refugees began streaming into the new sovereign state. Possibly as many as 170,000 Jewish displaced persons and refugees had immigrated to Israel by 1953. In December 1945, President Harry Truman issued a directive that loosened

quota restrictions on immigration to the US of persons displaced by the Nazi regime. Under this directive, more than 41,000 displaced persons immigrated to the United States; approximately 28,000 were Jews. In 1948, the US Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act, which provided approximately 400,000 US

immigration visas for displaced persons between January 1, 1949, and December 31, 1952. Of the 400,000 displaced persons who entered the US under the DP Act, approximately 68,000 were Jews. Other Jewish refugees in Europe emigrated as displaced persons or refugees to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, western Europe, Mexico, South America, and South Africa.

After the surrender of Nazi Germany, ending World War II, refugees and displaced persons searched throughout Europe for missing children. Thousands of orphaned children were in displaced persons camps. Many surviving Jewish children fled eastern Europe as part of the mass exodus to the western zones of occupied Germany, en route to the Yishuv (the Jewish settlement in Palestine). Through Youth Aliyah, thousands migrated to the Yishuv, and then to the state of Israel after its establishment in 1948.

Knowing his cause was hopeless, Adolf Hitler took his own life on April 30, 1945. Meanwhile, after World War II, many charges were put forth against the leaders of the Nazi party including Conspiracy, Crimes Against Peace, War Crimes, and Crimes Against Humanity. Many of the Nazi Party's top executives were found guilty at the trial and were sent to the death chamber. Many more Nazi scientists and doctors as well as SS Einsatz leaders were tried at Nuremburg. Some of those individuals were killed. Overall, around six million people were killed in the Holocaust.

The killing of these people not only took the lives of these six million people, it also affected millions and millions of other people who loved these Jews.

After liberation, many Jewish survivors feared to return to their former homes because of the antisemitism (hatred of Jews) that persisted in parts of Europe and the trauma they had suffered. Some who returned home feared for their lives. In postwar Poland, for example, there were a number of pogroms (violent anti-Jewish riots). The largest of these occurred in the town of Kielce in 1946 when Polish rioters killed at least 42 Jews and beat many others.

With few possibilities for emigration, tens of thousands of homeless Holocaust survivors migrated westward to other European territories liberated by the western Allies. There they were housed in hundreds of refugee centers and displaced persons camps such as Bergen-Belsen in Germany. The United Nations

Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the occupying armies of the United States, Great Britain, and France administered these camps.

A considerable number and variety of Jewish agencies worked to assist the Jewish displaced persons. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee provided Holocaust survivors with food and clothing, while the Organization for Rehabilitation through Training (ORT) offered vocational training. Refugees also formed their

own organizations, and many labored for the establishment of an independent Jewish state in Palestine.

The Jewish Brigade Group (a Palestinian Jewish unit of the British army) was formed in late 1944. Together with former partisan fighters displaced in central

Europe, the Jewish Brigade Group created the Brihah, an organization that aimed to facilitate the exodus of Jewish refugees from Europe to Palestine. Jews already living in Palestine organized "illegal" immigration by ship. British authorities intercepted and turned back most of these vessels, however. In 1947 the British forced the ship Exodus 1947, carrying 4,500 Holocaust survivors headed for Palestine, to return to Germany. In most cases, the British detained Jewish refugees denied entry into Palestine in detention camps on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

With the establishment of the State of Israel in May 1948, Jewish displaced persons and refugees began streaming into the new sovereign state. Possibly as many as 170,000 Jewish displaced persons and refugees had immigrated to Israel by 1953. In December 1945, President Harry Truman issued a directive that loosened

quota restrictions on immigration to the US of persons displaced by the Nazi regime. Under this directive, more than 41,000 displaced persons immigrated to the United States; approximately 28,000 were Jews. In 1948, the US Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act, which provided approximately 400,000 US

immigration visas for displaced persons between January 1, 1949, and December 31, 1952. Of the 400,000 displaced persons who entered the US under the DP Act, approximately 68,000 were Jews. Other Jewish refugees in Europe emigrated as displaced persons or refugees to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, western Europe, Mexico, South America, and South Africa.

After the surrender of Nazi Germany, ending World War II, refugees and displaced persons searched throughout Europe for missing children. Thousands of orphaned children were in displaced persons camps. Many surviving Jewish children fled eastern Europe as part of the mass exodus to the western zones of occupied Germany, en route to the Yishuv (the Jewish settlement in Palestine). Through Youth Aliyah, thousands migrated to the Yishuv, and then to the state of Israel after its establishment in 1948.

The Current State of Affairs

Some critics have expressed concern over the representations of Germany’s history, particularly in its texts for children. Shavit talks about the story of WWII that is familiar to most western world inhabitants, and claims that “this familiar story – with which non-German readers, whether American, British or Israeli, are acquainted – cannot be familiar to the German reader simply because the German historical discourse tells a completely different story” (287). This different story, which Shavit describes as the “story of the German victim in World Wars I and II,” was developed in the early 1960s. Shavit also brings up an interesting

point when he quotes an interview with the leader of the German republicans in 1994, who alleged “the eighty percent majority of the German people that

supported the Nazi regime during the Third Reich had become an even larger majority (ninety percent) that now claims to have supported the Jews during the Third Reich and offered them assistance (Shavit 288).

In his extensive article on the recovery of Jewish property in East Germany, however, Michael Meng describes the period in the late 1970s as a time of renewed social and political awareness of the Holocaust.

"Beginning in the late 1970s, the treatment of Jewish sites started to change as a result

of wider social, cultural, and foreign policy shifts in the GDR. The change

first occurred on the local level with grassroots, Christian-based organizations

showing interest in preserving Jewish sites. As early as the mid-1950s, the East

German Evangelical Church called for the preservation of Jewish sites, but it

was not until the 1970s that any serious reconstruction efforts took place. Two

organizations…were especially key in carrying out restoration projects and

creating a dialogue with East Germany's small Jewish community. Supported by the

Evangelical Church with some help from Catholic leaders, they organized local

projects to repair Jewish cemeteries and sponsored lectures on Jewish religion,

history, and culture. These groups formed part of a broader effort among church

leaders to confront the church's role during the Holocaust.95 In 1978, on the

fortieth anniversary of Kristallnacht, churches throughout the GDR hosted

discussions about the Nazi persecution of the Jews for the first time. In a

statement urging them to do so, the Conference for Evangelical Leadership noted,

"We call to the attention of the churches the fortieth anniversary of

Kristallnacht and remember it with shame. An enormous guilt lies on our

people.... In light of the failure and guilt of Christianity revealed by

[Kristallnacht], today everything must be done to spread knowledge about

historic and contemporary Jewry."

Meng goes on to point out that this spreading consciousness was not limited to the church and religious spheres. Translations of Polish texts about Nazi extermination tactics were appearing as early as the 1950s.

In chronicling the experience of being involved in Germany’s“Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe,” James Young describes the tortured ten year process, beginning with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when the project “gained the backing of both the Federal Government and the Berlin Senate” (Young 66). Young’s initial skepticism about appointing a single memorial to represent the immensity of the Holocaust is highlighted by his reaction to the failed selection of one out of a 528-design contest:

“Good, I wrote at the time. Better a thousand years

of Holocaust memorial competitions and exhibitions in Germany than any single

“final solution” to Germany’s memorial problem. This way, I reasoned, instead of

a fixed icon for Holocaust memory in Germany, the debate itself—perpetually

unresolved amid ever-changing conditions—might now be enshrined. Of course,

this was also a position that only an academic bystander could afford to take,

someone whose primary interest lay in perpetuating the process itself” (68).

Writing from his perspective in fall of 2002, Young concludes his discussion of the Memorial with his assessment of the actions of new generations of Germans:

From this American Jew’s perspective, this last year has

been a watershed for German memory and identity. No longer paralyzed by the

memory of crimes perpetrated in its name, Germany is now acting on the basis of

such memory: it participated boldly in NATO’s 1999 intervention against a new

genocide perpetrated by Milosevic’s Serbia; it has begun to change citizenship

laws from blood- to residency-based; and it has dedicated a permanent place in

Berlin’s cityscape to commemorate what happened the last time Germany was

governed from Berlin. Endless debate and memorialization are no longer mere

substitutes for actions against contemporary genocide but reasons for action.

This is something new, not just for Germany but for the rest of us, as

well (80).

point when he quotes an interview with the leader of the German republicans in 1994, who alleged “the eighty percent majority of the German people that

supported the Nazi regime during the Third Reich had become an even larger majority (ninety percent) that now claims to have supported the Jews during the Third Reich and offered them assistance (Shavit 288).

In his extensive article on the recovery of Jewish property in East Germany, however, Michael Meng describes the period in the late 1970s as a time of renewed social and political awareness of the Holocaust.

"Beginning in the late 1970s, the treatment of Jewish sites started to change as a result

of wider social, cultural, and foreign policy shifts in the GDR. The change

first occurred on the local level with grassroots, Christian-based organizations

showing interest in preserving Jewish sites. As early as the mid-1950s, the East

German Evangelical Church called for the preservation of Jewish sites, but it

was not until the 1970s that any serious reconstruction efforts took place. Two

organizations…were especially key in carrying out restoration projects and

creating a dialogue with East Germany's small Jewish community. Supported by the

Evangelical Church with some help from Catholic leaders, they organized local

projects to repair Jewish cemeteries and sponsored lectures on Jewish religion,

history, and culture. These groups formed part of a broader effort among church

leaders to confront the church's role during the Holocaust.95 In 1978, on the

fortieth anniversary of Kristallnacht, churches throughout the GDR hosted

discussions about the Nazi persecution of the Jews for the first time. In a

statement urging them to do so, the Conference for Evangelical Leadership noted,

"We call to the attention of the churches the fortieth anniversary of

Kristallnacht and remember it with shame. An enormous guilt lies on our

people.... In light of the failure and guilt of Christianity revealed by

[Kristallnacht], today everything must be done to spread knowledge about

historic and contemporary Jewry."

Meng goes on to point out that this spreading consciousness was not limited to the church and religious spheres. Translations of Polish texts about Nazi extermination tactics were appearing as early as the 1950s.

In chronicling the experience of being involved in Germany’s“Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe,” James Young describes the tortured ten year process, beginning with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when the project “gained the backing of both the Federal Government and the Berlin Senate” (Young 66). Young’s initial skepticism about appointing a single memorial to represent the immensity of the Holocaust is highlighted by his reaction to the failed selection of one out of a 528-design contest:

“Good, I wrote at the time. Better a thousand years

of Holocaust memorial competitions and exhibitions in Germany than any single

“final solution” to Germany’s memorial problem. This way, I reasoned, instead of

a fixed icon for Holocaust memory in Germany, the debate itself—perpetually

unresolved amid ever-changing conditions—might now be enshrined. Of course,

this was also a position that only an academic bystander could afford to take,

someone whose primary interest lay in perpetuating the process itself” (68).

Writing from his perspective in fall of 2002, Young concludes his discussion of the Memorial with his assessment of the actions of new generations of Germans:

From this American Jew’s perspective, this last year has

been a watershed for German memory and identity. No longer paralyzed by the

memory of crimes perpetrated in its name, Germany is now acting on the basis of

such memory: it participated boldly in NATO’s 1999 intervention against a new

genocide perpetrated by Milosevic’s Serbia; it has begun to change citizenship

laws from blood- to residency-based; and it has dedicated a permanent place in

Berlin’s cityscape to commemorate what happened the last time Germany was

governed from Berlin. Endless debate and memorialization are no longer mere

substitutes for actions against contemporary genocide but reasons for action.

This is something new, not just for Germany but for the rest of us, as

well (80).

A Timeline of the Holocaust & Other Relevent Events

1900sAlthough Antisemitism existed before this period, it was in the early 1900s that a new form emerged, a form that "falsely accused the Jews of being the carriers of sickness, economic crisis, poverty, and political conflicts" (Byers 5-6)

1914-1918Germany's initiation and subsequent loss of WWI plunged the country into political and socioeconomic uncertainty, creating an environment in which the new form of Antisemitism was latched onto in order to provide a scapegoat

1918The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was a fabricated text purporting to be the work of a Jewish secret society intent on taking over the world. It was written in 1895 for the Czar in Russia, but widely distributed in the rest of the world. Germany published The Protocols in 1918

1921Adolf Hitler, after joining the movement in 1919, elected head of the National Socialist German Workers' Party, abbreviated to "Nazi" from the party name's first word, Nazional

1922JUNE 24

Walter Rathenau, a Jewish industrialist who aided Germany's war effort (and was thereafter appointed first as the reconstruction minister, then foreign minister), faced mass demonstrations of protest, and, ultimately, assassination 1923November

Hitler attempted to take control of the government in the Beer Hall Putsch, which left sixteen party members and three policemen dead, and Hitler breifly a fugitive before he was caught and sent to serve a token prison sentence. The same year, three-hundred and fifty Jews were driven out of their homes in the German state of Bavaria 1929In 1920, the Nazi party had sixty members to its name. By 1929, there were one-hundred and seventy-eight thousand registered Nazi party members

1933January 30

Hitler handed the chancellorship of Germany February 27 The Reichstag Building was set on fire; the crime was blamed on a Nazi-identified communist, but the question remains whether Hitler's Storm Troops were responsible February 28 Hitler pushes through "For the protection of People and State" and succeeds in abolishing such civil liberties as freedom of speech, assembly, and press March 22 The opening of the first concentration camp: Dachau March 23 Hitler uses violence and intimdation to ensure the passage of the Enabling Act, giving his personally led cabinet total authority for four years. The act was passed by a vote of 441 to 94 April 1 At the instigation of the Nazi newspaper, and with the "encouragement" of the storm troopers, a nation-wide boycott of Jewish businesses, whether they were medical practices, law firms, or shops, took place April 7 Government workers of "non-Aryan descent" purged by the method of forced retirement - other laws curtailing Jewish rights to education and various lines of professions soon followed 1934August 2

Even the pretense of reining in Hitler's power abandoned when President Hindenburg died and Hitler declared himself Fuhrer, as the cabinet had conveniently linked the office of the president with that of the chancellor the day before 1935September 15

The Nuremburg Laws were passed: one law forbade the marriage or sexual relationship of a German and a Jew; the other denied people of Jewish blood the right to citizenship. The original two were supplemented by thirteen more decrees that followed over a span of eight years. 1938Jews were required to add "Israel" and "Sarah" to male and female names respectively, and were forced to register all their property

The Nazi's propagandistic text for children, Der Giftpilz (The Poison Mushroom), published for the purpose of instilling prejudice in younger generations March 13 Germany annexed Austria June Hitler personally ordered destruction of Munich's main synagogue. In the days soon following, fifteen hundred Jews with minor police records forced into concentration camps July 6-15 Franklin D. Roosevelt called international conference in Evian, France, to discuss Jewish refugees who were not permitted to emigrate with any of their possessions, and who thus had become a depressive factor in the economy. While previously tolerant, if not welcoming, countries began to turn away from the refugees, countries such as Australia and Switzerland made their unwillingness to get involved and outright antipathy clear; the Australian representative is reported to have said, "As we we have no racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one" (Byers 52). October 28 Deportation begins, starting with Polish Jews November 9-10 Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass: supposedly in response to an attack on the German Embassy in Paris (the perpetrator himself acting in response to the brutal deportation of his Jewish parents), members of Hitler's armed forces flooded into the streets dressed as civilians and attacked Jewish businesses, homes, religious centers, and people November 12 Jewish community fined the equivalent of $400 million to pay for the damages inflicted against them on Kristallnacht 1939March 15

Czechoslovakia becomes occupied territory of Germany August Hitler signs secret order allowing doctors to euthanize a select cross-section of patients, including "People who were incurably sick, physically handicapped, mentally ill, or simply old" (Byers 89). Experimentation by SS officer Christian Wirth lead to development of the gas chamber August 23 Political by-play produces a surprise nonaggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union September 1 Free from threat of Soviet reprisals, Hitler initiated shock-and-awe campaign in Poland September 27 Poland's last holdout, Warsaw, surrendered November 23 Jews in sections of Poland forced to wear Star of David 1940April 30

Ghetto in Lodz, Poland, sealed November 15 Warsaw ghetto sealed 1941May

The Einsatzgruppen, previously a political arm of the police force, undergoes a restructuring in order to prepare for the invasion of Russia. Their orders were to round up and execute "hostile inhabitants," a group that included Soviet leadership figures, Jews, Gypsies, and the handicapped people June 22 Having secured a stronghold in Poland, Hitler proceeded to turn on the Soviet Union Septemmber 28-29 Babi Yar ravine massacre: Jewish residents of Kiev given "resettlement" order; when they reported in, they were marched to Babi Yar, shot, and pushed in. Babi Yar was the largest recorded massacre perpetrated by the Einsatzgruppen One Einsatzgruppen leader "confessed that the executions were 'a moral strain' for his men" (Byers 87) October Average daily rations for ghetto inhabitants reduced from eleven hundred calories to eight hundred calories December 8 The first extermination camp, outside the Polish village Chelmno, begins to gas people. "Its victims were told that they were going to be taken to Germany, where they would find work. First, however, they needed shower and put on clean clothes" (Byers 90). 1942January 20

Wannsee Conference outside Berlin discussed the details of implementing the Final Solution March 16 In Poland, extermination camp Belzec was opened. May Extermination camp Sobibor opened. July 23 Extermination camp Treblinka opened. Later that year, gas chambers were installed in both Auschwitz and Madjanek. October Himmler gave the order to move all Jews in concentration camps within German borders to Auschwitz. 1943April 19 - May 16

Warsaw ghetto "liquidated" September - November Ghettos in occupied Soviet Union followed suit. 1944July 24

Soviets liberated Majdanek. 1945April 30

Hitler committed suicide. May 8 Allies accepted Germany's unconditional surrender. November 20 Trials for war criminals with an international tribunal began at Nuremberg. |

Glossary of Terms

Antisemitism: Hatred toward, or discrimination of Jews.

Aryan: Originally, people speaking certain languages.The Nazis appropriated the term to mean a Germanic background, typically tall, blond, and blue-eyed

Auschwitz: One of the largest extermination centers of a number of labor and extermination camps set up in Poland

Babi Yar: A ravine on the outskirts of Kiev, in the Soviet Union, where more than thirty-three thousand Jews were massacred on September 29-30, 1941

Chancellor: One of the two highest offices in Germany's Weimar Republic (the other being president)

Clandestine: Kept or done in secret often to conceal an illicit or improper purpose.

Concentration camp: Prison for political and religious opponents of the Nazi government, also used for ethnic and racial "enemies"

Einsatzgruppen: (Action Groups) mobile units of police that followed the German Army into conquered territories. After the German invasion of Russia, they killed Jewish civillians and others by the thousands

Euthanasia: The practice of deliberately killing someone who is suffering from an incurable condition. The Nazis used the term for the killing of physically and mentally handicapped and the aged

Final solution: Euphamism for the planned killing of all the Jews of Europe

Fuhrer: (Leader) Hitler became Fuhrer of the Nazi party and, as chancellor and president of Germany, adopted the title "The Fuhrer"

Ghetto: Sections of cities into which the Nazis forced all Jews. The areas were surrounded by barbed wire or walls, and no one was allowed to leave

Holocaust: The attempt by the Nazi government to completely destroy the Jews of Europe during WWII

Judenrat: Jewish council in the ghetto.

Kindertransport: A non-profit organization of child holocaust survivors who were sent out of Germany, without their parents.

Labor camp: Concentration camp in which prisoners were forced to perform labor for the Nazis

Partisan: A fervent, sometimes militant supporter or proponent of a party, cause, faction, person, or idea.

Nazi: A member of, or pertaining to, the National Socialist German Worker's party

Nuremberg laws: Two laws, followed by thirteen supplementary decrees, that distinguished between "Aryans" and Jews and deprived "non-Aryans" of civil liberties

Nuremberg trials: Trial of 22 of the most prominent Nazi leaders after WWII, by military judges of the US, UK, France, and Soviet Union

Storm troops: Nazi private police force, also called Sturmabteilung and Brownshirts

Synagogue: A Jewish house of worship

Transit Camp: Temporary way station for the prisoners.

Wannsee Conference: Gathering of Nazi leaders outside Berlin at which the details of implementing the Final Solution were decided

Weimar Republic: The democratic government of Germany between the end of WWI and Hitler's establishment of the Third Reich in 1933

Aryan: Originally, people speaking certain languages.The Nazis appropriated the term to mean a Germanic background, typically tall, blond, and blue-eyed

Auschwitz: One of the largest extermination centers of a number of labor and extermination camps set up in Poland

Babi Yar: A ravine on the outskirts of Kiev, in the Soviet Union, where more than thirty-three thousand Jews were massacred on September 29-30, 1941

Chancellor: One of the two highest offices in Germany's Weimar Republic (the other being president)

Clandestine: Kept or done in secret often to conceal an illicit or improper purpose.

Concentration camp: Prison for political and religious opponents of the Nazi government, also used for ethnic and racial "enemies"

Einsatzgruppen: (Action Groups) mobile units of police that followed the German Army into conquered territories. After the German invasion of Russia, they killed Jewish civillians and others by the thousands

Euthanasia: The practice of deliberately killing someone who is suffering from an incurable condition. The Nazis used the term for the killing of physically and mentally handicapped and the aged

Final solution: Euphamism for the planned killing of all the Jews of Europe

Fuhrer: (Leader) Hitler became Fuhrer of the Nazi party and, as chancellor and president of Germany, adopted the title "The Fuhrer"

Ghetto: Sections of cities into which the Nazis forced all Jews. The areas were surrounded by barbed wire or walls, and no one was allowed to leave

Holocaust: The attempt by the Nazi government to completely destroy the Jews of Europe during WWII

Judenrat: Jewish council in the ghetto.

Kindertransport: A non-profit organization of child holocaust survivors who were sent out of Germany, without their parents.

Labor camp: Concentration camp in which prisoners were forced to perform labor for the Nazis

Partisan: A fervent, sometimes militant supporter or proponent of a party, cause, faction, person, or idea.

Nazi: A member of, or pertaining to, the National Socialist German Worker's party

Nuremberg laws: Two laws, followed by thirteen supplementary decrees, that distinguished between "Aryans" and Jews and deprived "non-Aryans" of civil liberties

Nuremberg trials: Trial of 22 of the most prominent Nazi leaders after WWII, by military judges of the US, UK, France, and Soviet Union

Storm troops: Nazi private police force, also called Sturmabteilung and Brownshirts

Synagogue: A Jewish house of worship

Transit Camp: Temporary way station for the prisoners.

Wannsee Conference: Gathering of Nazi leaders outside Berlin at which the details of implementing the Final Solution were decided

Weimar Republic: The democratic government of Germany between the end of WWI and Hitler's establishment of the Third Reich in 1933

Bibliography of Children's Literature

Once by Morris Gleitzman

Felix, a Jewish boy in Poland in 1942, is hiding from the Nazis in a Catholic

orphanage. The only problem is that he doesn't know anything about the war,

and thinks he's only in the orphanage while his parents travel and try to

salvage their bookselling business. And when he thinks his parents are in

danger, Felix sets off to warn them--straight into the heart of Nazi-occupied

Poland.

To Felix, everything is a story: Why did he get a whole carrot in his soup?

It must be sign that his parents are coming to get him. Why are the Nazis

burning books? They must be foreign librarians sent to clean out the

orphanage's outdated library. But as Felix's journey gets increasingly

dangerous, he begins to see horrors that not even stories can explain.

Despite his grim suroundings, Felix never loses hope. Morris Gleitzman

takes a painful subject and expertly turns it into a story filled with love,

friendship, and even humor

orphanage. The only problem is that he doesn't know anything about the war,

and thinks he's only in the orphanage while his parents travel and try to

salvage their bookselling business. And when he thinks his parents are in

danger, Felix sets off to warn them--straight into the heart of Nazi-occupied

Poland.

To Felix, everything is a story: Why did he get a whole carrot in his soup?

It must be sign that his parents are coming to get him. Why are the Nazis

burning books? They must be foreign librarians sent to clean out the

orphanage's outdated library. But as Felix's journey gets increasingly

dangerous, he begins to see horrors that not even stories can explain.

Despite his grim suroundings, Felix never loses hope. Morris Gleitzman

takes a painful subject and expertly turns it into a story filled with love,

friendship, and even humor

Then by Morris Gleitzman

Felix and Zelda have escaped the train to the death

camp, but where do they go now? They're two runaway kids in Nazi-occupied

Poland. Danger lies at every turn of the road.

With the help of a woman named Genia and their active

imaginations, Felix and Zelda find a new home and begin to heal, forming a new

family together. But can it last?

Morris Gleitzman's winning characters will tug at

readers' hearts as they struggle to survive in the harsh political climate of

Poland in 1942. Their lives are difficult, but they always remember what

matters: family, love, and hope.

camp, but where do they go now? They're two runaway kids in Nazi-occupied

Poland. Danger lies at every turn of the road.

With the help of a woman named Genia and their active

imaginations, Felix and Zelda find a new home and begin to heal, forming a new

family together. But can it last?

Morris Gleitzman's winning characters will tug at

readers' hearts as they struggle to survive in the harsh political climate of

Poland in 1942. Their lives are difficult, but they always remember what

matters: family, love, and hope.

Rose Blanche by Roberto Innocenti

In wartime Germany, Rose Blanche witnesses the mistreatment of a little boy, and

follows the truck that takes him to a camp. Secretly, Rose Blanche brings him

and other children food.

"An excellent book to use not only to teach about the

Holocaust, but also about living a life of ethics, compassion, and

honesty".--School Library Journal. Full color

follows the truck that takes him to a camp. Secretly, Rose Blanche brings him

and other children food.

"An excellent book to use not only to teach about the

Holocaust, but also about living a life of ethics, compassion, and

honesty".--School Library Journal. Full color

Terrible Things: An Allegory of the Holocaust by Eve Bunting

This unique introduction to the Holocaust encourages young children to stand up

for what they think is right, without waiting for others to join them.

for what they think is right, without waiting for others to join them.

The Devil's Arithmetic by Jane Yolan

This critically acclaimed novel by award-winning author Jane Yolen is now

available in a beautifully designed new edition. Hannah dreads going to her

family's Passover Seder—she's tired of hearing her relatives talk about the

past. But when she opens the front door to symbolically welcome the prophet

Elijah, she's transported to a Polish village in the year 1942, where she

becomes caught up in the tragedy of the time.

"Readers will come away with a sense of tragic history

that both disturbs and compels." --Booklist

available in a beautifully designed new edition. Hannah dreads going to her

family's Passover Seder—she's tired of hearing her relatives talk about the

past. But when she opens the front door to symbolically welcome the prophet

Elijah, she's transported to a Polish village in the year 1942, where she

becomes caught up in the tragedy of the time.

"Readers will come away with a sense of tragic history

that both disturbs and compels." --Booklist

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas by John Boyne

Berlin 1942

When Bruno returns home from school one day, he discovers

that his belongings are being packed in crates. His father has received a

promotion and the family must move from their home to a new house far far away,

where there is no one to play with and nothing to do. A tall fence running

alongside stretches as far as the eye can see and cuts him off from the strange

people he can see in the distance.

But Bruno longs to be an explorer and decides that there must

be more to this desolate new place than meets the eye. While exploring his new

environment, he meets another boy whose life and circumstances are very

different to his own, and their meeting results in a friendship that has

devastating consequences.

When Bruno returns home from school one day, he discovers

that his belongings are being packed in crates. His father has received a

promotion and the family must move from their home to a new house far far away,

where there is no one to play with and nothing to do. A tall fence running

alongside stretches as far as the eye can see and cuts him off from the strange

people he can see in the distance.

But Bruno longs to be an explorer and decides that there must

be more to this desolate new place than meets the eye. While exploring his new

environment, he meets another boy whose life and circumstances are very

different to his own, and their meeting results in a friendship that has

devastating consequences.

Sources

http://www.ushmm.org/outreach/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007689

East Germany's Jewish Question: The Return and Preservation of Jewish Sites in East Berlin and Potsdam, 1945-1989

Author(s): Michael Meng

Reviewed work(s):Source: Central European History, Vol. 38, No. 4 (2005), pp. 606-636

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Conference Group for Central European History of the American Historical Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141154

Germany's Holocaust Memorial Problem—and Mine

Author(s): James E. Young

Reviewed work(s):Source: The Public Historian, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Fall 2002), pp. 65-80

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2002.24.4.65

Byers, Ann.

The Holocaust Overview. Springfield: Enslow Publishers, Inc., 1998.

Print.

http://www.amazon.com/Then-Morris-Gleitzman/dp/0805090274/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1348429009&sr=8-1&keywords=then+morris+gleitzman

http://www.amazon.com/Once-Morris-Gleitzman/dp/0805090266/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1348429084&sr=1-1&keywords=once+morris+gleitzman

http://www.amazon.com/Blanche-Creative-Editions-Roberto-Gallaz/dp/1568461895/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1348429113&sr=1-1&keywords=rose+blanche

http://www.amazon.com/Terrible-Things-Allegory-Holocaust-Classic/dp/0827603258/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1348429146&sr=1-1&keywords=terrible+things

http://www.amazon.com/Devils-Arithmetic-Jane-Yolen/dp/0140345353

http://www.amazon.com/The-Striped-Pajamas-John-Boyne/dp/0385751060

East Germany's Jewish Question: The Return and Preservation of Jewish Sites in East Berlin and Potsdam, 1945-1989

Author(s): Michael Meng

Reviewed work(s):Source: Central European History, Vol. 38, No. 4 (2005), pp. 606-636

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Conference Group for Central European History of the American Historical Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20141154

Germany's Holocaust Memorial Problem—and Mine

Author(s): James E. Young

Reviewed work(s):Source: The Public Historian, Vol. 24, No. 4 (Fall 2002), pp. 65-80

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2002.24.4.65

Byers, Ann.

The Holocaust Overview. Springfield: Enslow Publishers, Inc., 1998.

Print.

http://www.amazon.com/Then-Morris-Gleitzman/dp/0805090274/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1348429009&sr=8-1&keywords=then+morris+gleitzman

http://www.amazon.com/Once-Morris-Gleitzman/dp/0805090266/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1348429084&sr=1-1&keywords=once+morris+gleitzman

http://www.amazon.com/Blanche-Creative-Editions-Roberto-Gallaz/dp/1568461895/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1348429113&sr=1-1&keywords=rose+blanche

http://www.amazon.com/Terrible-Things-Allegory-Holocaust-Classic/dp/0827603258/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1348429146&sr=1-1&keywords=terrible+things

http://www.amazon.com/Devils-Arithmetic-Jane-Yolen/dp/0140345353

http://www.amazon.com/The-Striped-Pajamas-John-Boyne/dp/0385751060